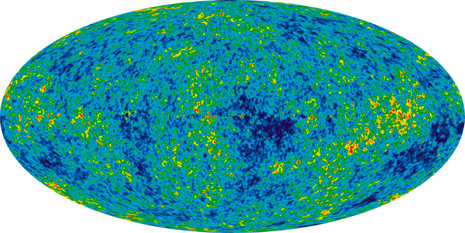

The detailed, all-sky picture of the infant universe created from seven years of NASA's WMAP data (Image: NASA/WMAP)

Cosmologists in London say they've developed a new computer algorithm which could help them find proof of a parallel universe.

The concept of multiple universes is not new. The multiverse - also called the meta-universe or metaverse – is a theory that suggests the universe is actually a series of multiple or alternative universes, with our own universe being just one of many.

American philosopher and psychologist William James came up with the term back in 1895.

The universes that are contained within the multiverse are sometimes called parallel universes.

Some of the current multiverse theories propose that our and other universes are contained inside a bubble, where known fundamental physical constants, and even the basic laws of nature, might vary.

Theories of the the multiverse are found, not only in sciences like cosmology, physics and astronomy, but also within the study of religion, philosophy, trans-personal psychology and in literature, usually science fiction.

Research papers issued by a team based at University College London (UCL), Imperial College London and the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, outline just how one can search for signatures of other universes.

According to the research team, the new computer algorithm searches the skies for the tell-tale signatures of collisions between "bubble universes".

Armed with this new tool, physicists are now searching for disk-like patterns in the heat radiation left over from the Big Bang – which is known as cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation – for evidence of collisions between other universes and our own.

If the scientists prove successful at detecting signs of bubble universe collisions, they would then have have proof of the multiverse.

The study's authors stress that their initial results are not conclusive enough to either rule out the multiverse or to definitively detect the imprint of a bubble collision.

Scientists Find What's Behind Our Feeling Run-down and Tired When Sick

(Image: Alison Young via Flickr)

Scientists have identified what makes us feel bad when we're sick and, as a result, now have an idea of how to make us feel better.

It turns out that a signaling system in the brain, which is known to regulate sleep, is also responsible for inducing lethargy during illness, according to research from the Doernbecher Children's Hospital at the Oregon Health & Science University. The finding could lead to the development of new drugs to combat lethargy brought on by illness.

That sluggish, run-down feeling we get when we are sick? It's actually a natural survival mechanism.

Fever, lack of appetite and lethargy are signs of our body's highly organized strategy to give up certain biological and physiological priorities in order to give us with the greatest chance of survival.

Authors of this study say that their findings are particularly meaningful because they open up the possibility that a new class of drugs - originally developed to treat sleep disorders like narcolepsy - can also reverse the inactivity and exhaustion brought on by acute illness and restore the patient's energy and motivation.

New Material Conserves Energy and Controls Room Temperature

(Photo: Associated Press)

Researchers at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China (UNNC) have developed a new material that may be able to conserve energy and cut down on the cost of heating and cooling buildings.

The new material called non-deformed energy storage phase change material (PCM) is able to store and then release heat according to specific temperature requirements.

The researchers say that the new material, which they say could be made inexpensively, can store more energy and has a faster thermal response than other like materials.

So how does this new stuff work? for example, if the optimum temperature in a room is 22°C, the material can be fixed so that it starts to absorb any excess heat above that temperature and then release the it when the room temperature dips beneath that temperature level.

Researchers at the University's Centre for Sustainable Energy Technologies developed this new material and they say that it could be applied anywhere, from walls and roofs to wallpaper in new buildings and in old.

>>> Read more

Are Pets Really Good for People?

(Photo: Yukari via Flickr)

Finally, it's pretty obvious people form a special bond with their pets. In many households, the pet is considered to be an actual part of the family and is often pampered and treated just like another family member.

Conventional wisdom over the years has told us that pets are good for us, that they make us happier and enrich our lives.

But is there really such a thing as the "pet effect" on our mental and physical health?

The answer may be yes or it may be no – but according to a new article written by Harold Herzog, a Professor of Psychology at the Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, NC, there simply isn't strong evidence for the general claim that living with a pet makes for a happier, healthier or longer life.

Dr. Herzog's article is set to be published in a journal of the Association for Psychological Science. In it, he argues that existing research on pet ownership has produced very conflicting results.

While there are studies that do suggest that pet ownership is indeed associated positive aspects such as reduced rates of depression or lower blood pressure, there are other studies that suggest those who own pets are no better off than non-pet owners and, in fact may even be worse off in some ways.

In examining the inconsistencies between the two groups of studies, Dr. Herzog found that studies regarding pet ownership often have a number of basic methodological issues. Many of these studies use small, homogeneous samples, lack of appropriate control groups, and tend to rely on a participant's self-report to measure health and well-being.

He goes on to say that he noticed very few studies have used the kind of experimental design necessary to show that pets actually cause improvements in their owner's health and happiness.

Dr. Herzog says that to truly understand the effects that pets have on our lives, more rigorous research needs to be conducted.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario